In Charlotte Mason's third chapter on The Will, this often-quoted line appears:

"The simple, rectified Will, what our Lord calls 'the single eye,' would appear to be the one thing needful for straight living and serviceableness" (p. 138).It's a topic I've discussed previously on the blog. As we saw in the previous post, "Un-Will" is "all that we do or think, in spite of ourselves" (p. 140). We can't help ourselves, whatever it was just pops up or out, and we go along with it. All that we do out of our nature, or out of habit or custom, is not willed.

"Thus far we have seen, that, just as to reign is the distinctive quality of a king, so is to will the quality of a man. A king is not a king unless he reign; and a man is less than a man unless he will" (p. 140).We need to be careful here, because Charlotte Mason's approach to child training and early education begins with building good habits. Habit, Mason said elsewhere, is "a good servant but a bad master" (Philosophy of Education, p. 53). It's a tool for us to use, but not our default setting for important choices. If we have a habit of closing the door, we don't have to think about whether to close the door or not, and that's okay. If we have a custom of making a pot of tea in the afternoon, that's fine. To use my friend the DHM's phrase in a different context, we don't use a chainsaw to butter our bread. We need to be people of Will, to bypass the "tempting by-paths and strike ahead" (p. 139); but not everything in life needs to make use of the Will. It's a power tool.

Mason warns that being "turbulent" and "headstrong" is the opposite of being governed by Will. However, acting with Will and having a purpose outside of oneself does not rule out creativity, spontaneity, intuition, or even serendipity. It's those who unconsideringly act from habit, or who fly off with the latest popular idea, who are actually less creative and original. They are less free to act when the moment is right; they miss opportunities to fight boldly for a cause, to live out a principle. Those governed by Will are not bound to some kind of 24/7 scheduling with no surprises: they can act unexpectedly, but in ways that, seen in the big picture, make perfect sense. (But remember that Will is not necessarily moral, so the actions of a criminal or a terrorist can also make perfect sense.)

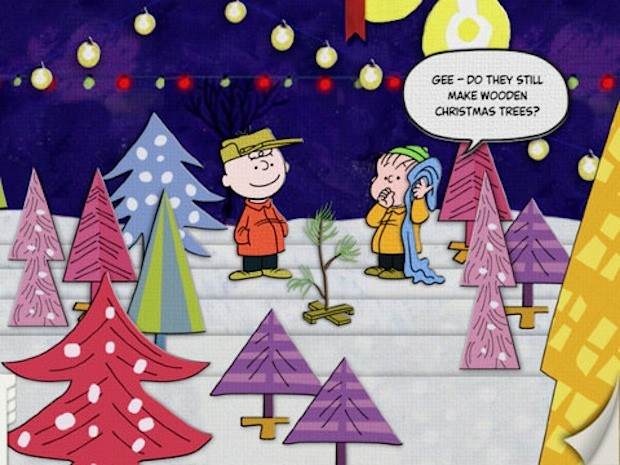

When I thought about that, here's the illustration that came to mind.

In "A Charlie Brown Christmas," Lucy, who wants only "real estate" for Christmas and who has cast herself as the Christmas Queen in the kids' play, seems to be the perfect example of "turbulent" and "headstrong." Lucy and her friends send Charlie Brown and Linus off to buy a "shiny aluminum Christmas tree," "maybe painted pink." But Charlie bypasses the shiny fakes and chooses a "wooden Christmas tree," the smallest and worst on the lot. "I think it needs me," he tells Linus. He has a principle and a purpose outside of himself: to care for something weak that needs help. To him, that's worth doing the unexpected, even though he second-guesses himself later when he is scolded and ridiculed by the other kids. They later have a change of heart and show the tree some love, which causes it to grow into the biggest, most beautiful Christmas tree ever.

A little tree and a little Will create a little Christmas magic.